By Associate Professor Laurie Laurenson

[Dr Laurenson is a retired Deakin University academic with research expertise in fish and fisheries biology. He has published more than 70 scientific research papers since the 1980s on various aspects of shark biology, fish biology and remote sensing.]

I wanted to get a better understanding of where Wannon Water got its idea that discharging partially treated water into Thunder Point was a good idea.

So I did a search on the internet and found the “Wannon Water Warrnambool STP Upgrade Mixing Zone Modelling And Outfall Assessment” document.

It’s really quite a long document but essentially looks at what biological (E. coli, Enterococci) and chemical (forms of phosphorus and nitrogen) contaminants are being discharged into the ocean and whether Wannon Water is following the rules, and will they be able into the future.

The report says “all is good” and that EPA regulations which stipulate that the contaminants should disperse within 300m of the outfall will be met.

I thought, “well that’s good” and I expected to see the three critical things that would influence dispersal of contaminants nicely organised and documented in the report. The three things being swell, winds and currents. Well, one of them was there!

I’ll digress here, because this is important.

Winds are the main driver of swell and have an extremely well documented history of inducing currents.

We all know the effect that a few days of SE winds have on the water temperature in Warrnambool (it’s freezing!). This is caused by wind-induced currents travelling from the SE to the NW and then the Coreolis Effect turning the current left, and offshore, and cold water coming up from the bottom.

Now when we have winds coming from the other directions (NW to SE) the reverse happens, currents follow the wind and the surface water turns in towards the coast, so it stays warm.

Back to the report…

The mixing of contaminants in the report relies on a circular (300m specified by the EPA) radius to disperse contaminants to acceptable levels (50 per cent of the time) based entirely on the capacity of oceanic swells to achieve the dispersal – not wind and currents.

A cursory look at where Warrnambool’s wind comes from across the year shows that they come from the SW quadrant 50 per cent or more of the time across each year.

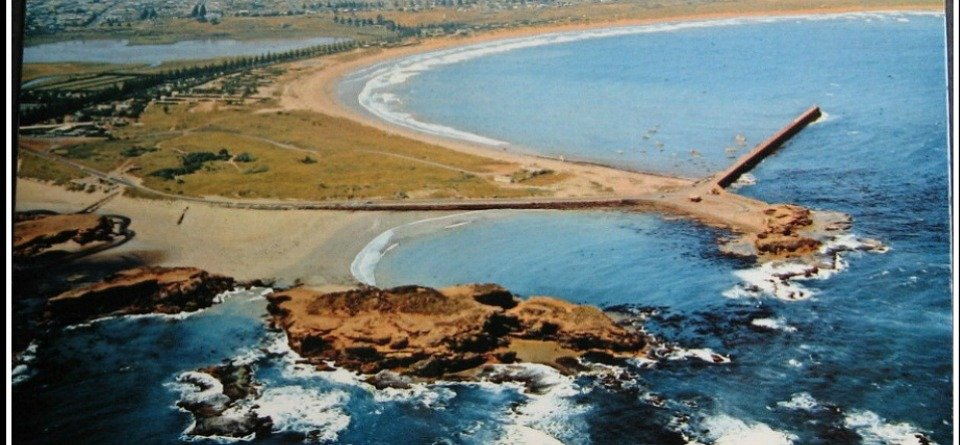

This means discharge at Shelly Beach will be blown towards the Warrnambool beaches at least one out of every two days.

The impact assessment report says that this is okay, since the closest high use beach in the area is the Flume roughly 3km away.

In fact the closest beach is Stingray Bay which is 1300m.

So here’s the problem.

On page 69 of the Wannon Water Report, it provides an “adopted minimum dilution rate” graphic which tells us how far the contaminants can spread.

This graphic is based on samples collected at a distance from the outfall of 400m (and less) with just a single sample taken at 750m.

Their predictions are based on three samples (presumably a few days in 2009, 2015 and 2016) that are assumed to be representative of the weather conditions across the entire year.

Their predictions are highly extrapolated outside their data range and based on simple linear regressions which are unlikely to be statistically significant (the significance has not been tested).

The science is poor at best.

The problem is that the degree of dispersal of contaminants beyond the 300m radius of the Wannon Water outfall has not been addressed in any meaningful way in that it excludes wind and currents, and further, the data that they have collected extrapolates well beyond the bounds of existing data.

It means that the report simply does not address the impact of the pollutants released from the outfall on the main recreational beaches of Warrnambool.

To be fair, the report states that it essentially focuses on the EPA stipulated boundary of 300m and that the pollutants do not exceed critical levels specified by the EPA for 50 per cent of the time.

However, the pollutant levels really need to be assessed at Stingray Bay and Lady Bay during wind and current conditions that will result in them being transported into these high use areas.

Given the prevailing wind conditions, this will happen at least every second day across every year.

And it’s not just the chemical and biological contaminants that will disperse in this way, it’s also the plastics that have repeatedly been released by the facility over many years.

You can find out more about the proposed treatment plant upgrade here and sign up for the online forum this Wednesday August 5 at 7pm.

Thanks for the update Laurie…..and your work Carol.

Interesting read, Laurie. I often walk, cycle, paddle and surf along parts of Thunder point and surrounds hoping that the correct measures and safety precautions are taken by government agencies or authorities to protect this coastline and marine life ( not just human safety) for future generations to enjoy. The ocean cannot simply dilute any human effluent and other rubbish released into this environment ( Just because we cannot observe direct, visual impacts, this doesn’t mean threats are evident to this area.) Wake up Wannon Water and start routine testing along this fragile coastline.

I doubt this and this is why. The predominant movement of Ocean currents moves in a Westerly direction and admittedly the swell does come from the SouthWest, however… It is evident to see that freshwater leaving the local rivers create rock reefs. They extend far out to sea at times. To the South South East of the Hopkins. Again, the Merri has created reefs as far out as LaBella reef and the Breakwater wall is built on those reefs. Same situation again for the Moyne river except that a lava flow took the river bed in the past at one point in time and stretched across the island there. I forget its name right now but where the lighthouse is. Because of this effect of the river water on the limestone at sea level each river enters the Ocean at a point. But we are speaking mainly about the Merri here at Point Pickering. The three islands at Point Pickering were once one land mass. A peninsula, so to speak. And like the other two rivers mentioned, not by coincidence the river exited into the Ocean on the Eastern side of the Points in the land. Wave action and the prevailing winds did eventually break through the Pickering Point peninsula and at that time the prevailing Westerly direction Ocean current started moving between the now islands carrying with it the freshwater exiting the Merri. This in turn started the formation of rock reefs behind Point Pickering and due to those waters becoming diluted with Ocean water moving towards Shelly beach the Rock reefs become less and less. Just a point of interest here. What I describe was the stasis until the Breakwater wall was built. The creation of that wall altered the natural flow of water between the islands coming from the East. What began at that time were sets of waves coming in through Stingray Bay and in the other direction through Lady Bay, or Worm Bay, as you please. But the wave action head to head became a sand bar underneath the Viaduct road. And the rest is History. I do not believe that effluent, bad as it may be will flow back between the islands towards Stingray Bay.

The longshore drift moves in an easterly direction – west to east. Edmund Gill established this in the 1970s and 80s by depositing red sand from central Australia at beaches along the western Victorian coast and recording its prevalence as it moved along the coast. With all respect, there is no need to confuse the issue.

A few things to add here regarding the wave modelling in the report. A bit dry, but important.

– The NOAA Wave Watch 3 (NWW3) model used as (the only) environmental input to the dilution modelling is a global open ocean model operating at a nominal resolution of 0.5 degrees (roughly 50 km on ground depending on latitude). Using this directly to model effluent dispersion over 100s of metres to kilometres in a nearshore environment is akin to brushing your teeth with a mop. Not the right tool for the job. The data (bathymetry and shoreline geometry) required to ‘downscale’ the NWW3 model and achieve best practice is freely available.

– The consultants acknowledge this oversight by throwing a ‘Hail Mary’ to a report where best practice was followed but with completely different goals :-

“Generally, there is a good qualitative agreement between the wave roses of the ‘dampened’ NWW3 data and the Water Technology (2012) nearshore waves. As such, the dampened dataset was deemed to be a

good representation of the wave climate likely to be experienced at the outfall site.”

Essentially this is like saying that (modelled) conditions 60km offshore at depths of 120m are suitable for assessing the way that effluent will be transported along a convoluted coastline in depths of several metres close to recreational beaches and areas of environmental significance. Any conclusions drawn from this modelling, which is inherently flawed, need to be questioned.